For most of the three decades since independence, the Central Asian “stans” and the countries in the Caucasus attracted little attention from western governments. The region was primarily of interest to adventurous travelers and historians. That started to change with the entry of international oil majors to help Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan develop their oil and gas resources, ensuring those two names became somewhat more familiar, and of greater importance to western economies.

Recognition of strategic importance, on a much larger scale, is now taking place. Central Asia is home to many of the so-called critical minerals, or CRAMs, that western economies need to sustain their technology, environmental and metallurgical industries. For decades they have been sourcing these materials from China, the world’s dominant producer, but both Washington and Brussels now want to reduce that reliance, at a time when China is also starting to ban or restrict some exports.

In 2022, the United States adopted the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). It aims to strengthen the domestic supply chain for critical minerals by offering incentives such as tax credits for their domestic production and extraction in the United States or in friendly nations. The Act also seeks to streamline permitting processes for these projects and incorporates rules to restrict the involvement of foreign entities, such as from China and Russia, in the CRAM supply chain.

In 2024, the EU passed the European Critical Raw Materials Act. It aims to reduce EU reliance on single suppliers like China by diversifying the supply of 34 critical raw materials. The Act sets ambitious domestic targets for extraction, processing, and recycling, and promotes strategic partnerships with other countries to build resilient and sustainable supply chains for environmental and digital transitions.

Zhana Kazakhstan

Central Asia is already important. Kazakhstan is the world’s biggest producer of uranium, accounting for 44 percent of world supply last year (Canada was next with a 15 percent share). But almost all its uranium is processed in Russia and then exported to the nuclear energy sector in the U.S. and the EU. Since early 2022, both are actively looking at how they can directly source more uranium from Central Asia, and to get it to the west across the Caspian to either Georgian or Turkish ports.

Kazakhstan also has the potential to be a major producer of various critical minerals such as manganese ore, chromium, lead, zinc, titanium, beryllium, silicon, and copper, with specific high global rankings mentioned for manganese ore (38.6 percent of global reserves), chromium (30 percent), lead (20 percent), zinc (12.6 percent), titanium (8.7 percent), and silicon.

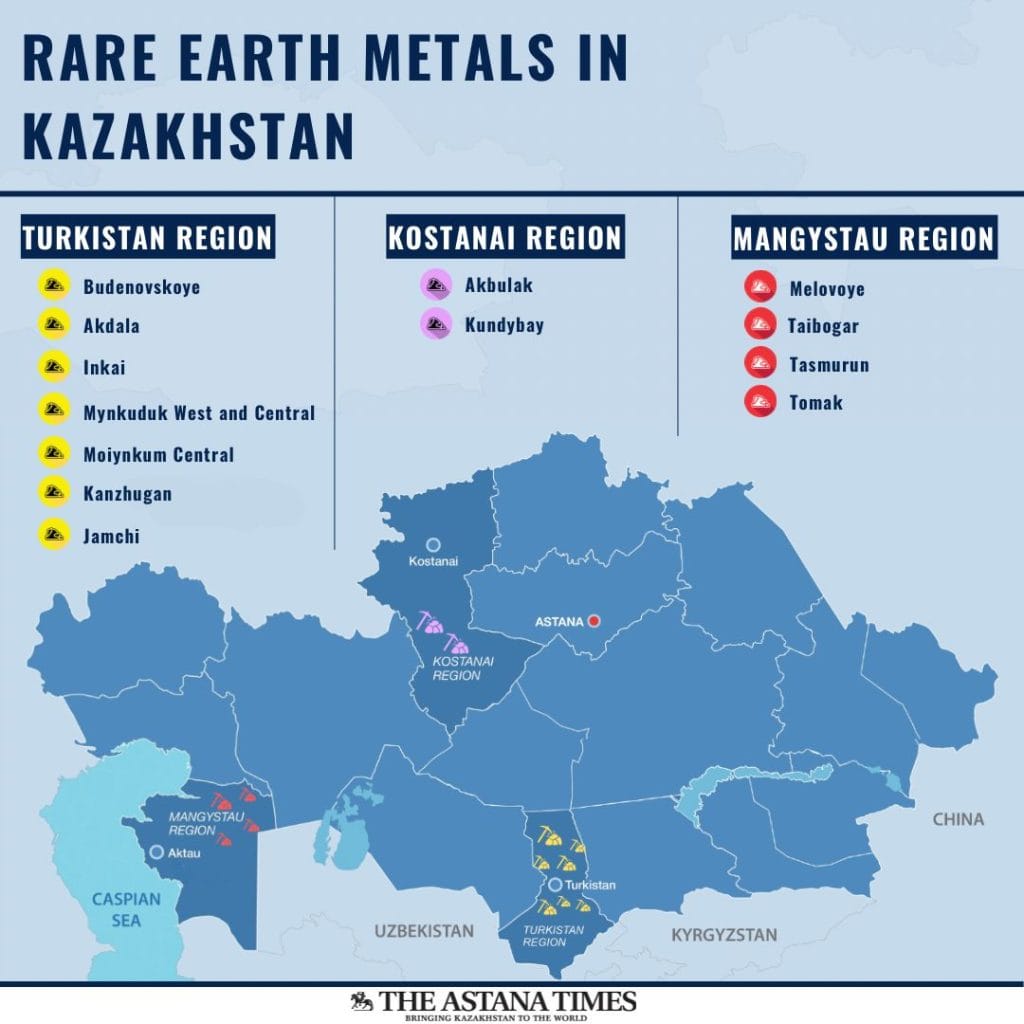

In April this year, Kazakhstan announced the discovery of a substantial rare earth metals deposit at the Zhana Kazakhstan site, located approximately 420 kilometers from the capital. This deposit is estimated to contain over 20 million metric tons of rare earth elements, including neodymium, cerium, lanthanum, and yttrium. This discovery positions Kazakhstan among the top countries globally in terms of rare earth reserves, following China and Brazil.

Uzbekistan seeks foreign investment in CRAMs

Uzbekistan is also exploring opportunities for foreign investment in critical minerals. In March this year, President approved a strategic plan to expand the country’s critical mineral resource base and boost value-added production. The country has identified deposits of over 30 key industrial metals, including tungsten, molybdenum, magnesium, lithium, germanium, graphite, vanadium, and titanium. Over the next three years, 76 projects worth $2.6 billion are to be launched, targeting 28 rare minerals. These include initiatives to enrich raw materials using modern technologies, improve mineral purity, and generate high-value products. Plans also include the creation of “technoparks” in Tashkent and Samarkand to integrate the full supply chain, from raw materials to final products.

During a recent official visit to the United States, Uzbekistan’s President Shavkat Mirziyoyev signed a series of agreements with American companies focused on the extraction and development of critical minerals. According to the Uzbek Ministry of Investments, the deals encompass joint cooperation in mineral exploration, investments in resource extraction, construction of high-pressure grinding rolls, ore processing complexes, technology transfer, and the development of value-added production from critical raw materials. The agreements also include commitments to train and upskill Uzbek specialists.

Uzbekistan and the EU held a summit in Samarkand last year where a commitment to also jointly develop critical minerals was agreed in principle. It is expected that a more specific agreement will be approved at the next summit planned for this autumn.

Tajikistan is positioning itself as a future supplier of critical raw materials and announced plans to attract foreign investment to develop its reserves of lithium, tungsten, nickel, and other CRAMS. Authorities report that Tajikistan holds around 800 mineral deposits, albeit yet to be proven independently, including seven considered unique to the country. Tajikistan is of particular interest to western nations because it is the world’s second largest supplier of antimony, the material critical in the production of munitions. China has been the main supplier to the U.S. and EU defense sectors but has started to curtail exports of this material from earlier this year.

Tajikistan’s uranium sector

Also of particular strategic interest to western governments is Tajikistan’s uranium sector, long shrouded in secrecy. Though estimates vary widely, it is believed the country holds substantial uranium reserves, and, even more importantly, it is home to a Soviet-era uranium enrichment facility — Vostokredmet — which the government plans to modernize. if reactivated, this plant would become Central Asia’s only uranium processing site, offering an alternative to Russian facilities for countries like Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Kyrgyzstan does not plan to be left behind. This year President Japarov met with senior EU officials recently and both sides agreed, in principle, for the development of critical raw materials and rare earth minerals. However, no specific deals have yet been agreed.

Japarov proclaims that Kyrgyzstan possesses reserves of rare and valuable metals (claims yet to be proven) and is ready to provide Europe with access to these resources. He suggested formalizing this cooperation through a dedicated partnership or a “roadmap,” similar to existing agreements between the EU and Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan.

But Kyrgyzstan has a greater problem in trying to attract investors because of its poor track record with investors in the mine sector. 90 percent of the Kyrgyz Republic’s existing mining output is gold, and most of this comes from the Kumtor mine. This was created by a Western investor, Cameco (whose gold assets were later spun off into Canada based Centerra), but the project was nationalized in 2021. This project has been controversial in the Kyrgyz Republic for decades over alleged environmental damage and corruption. As a result, there is considerable popular distrust over future mining projects inside the country and amongst international mining companies.

What is clear is that when it comes to critical minerals, the stans have barely scratched the surface. The Central Asian countries clearly have an abundance of natural resources. But except for Uranium production in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan (smaller) and antimony in Tajikistan), they have hardly developed production.

All countries have a shopping list of potential projects that are always brought out during the various Central Asia summits with partners like the EU and the U.S., but so far there are only talks.

Weaning off China dependence

The countries in the Caucasus do not have critical minerals in commercial quantities. But the region is expected to play a key role in the west’s efforts to wean itself off China dependency. The only route to export minerals out of Central Asia, which avoids both the northern route via Russia and the southern route via Iran, is across the Caspian Sea and via Baku to a Georgian port on the Black Sea. Soon that route will be complemented with another option, the Zangezur Corridor. This route will allow a quicker transit from Azerbaijan to a Turkish port on the Mediterranean Sea that bypasses the congested Bosphorus. Armenia’s Prime Minister and Azerbaijan’s President recently signed a Joint Declaration in the White House, witnessed by President Trump, to open the route across southern Armenia. Characteristically, Trump suggested renaming it the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP). The existing Baku-Georgia and the potential TRIPP routes ensure that the Caucasus are every bit as important in the Critical Mineral supply chain as the producing stans.

The deterioration in trust between China, Russia and the west is a big opportunity for the stans and the Caucasus. The abundance of Critical Minerals offers not only economic and export potential but also western co-investment in value-added processing and transportation. Of course, being an important supplier of CRAMS to the west is also useful when it comes to geopolitical bartering. As Azerbaijan, an important and growing supplier of gas to the EU, has already discovered, who in Washington or Brussels will criticize political and media suppression in Central Asia or the Caucasus when they need Critical Minerals for their technology and defense industries?